- Home

- Guide to the NQF

- Section 5: Regulatory Authority Powers

- 15. Good regulatory practice

Table of contents

- Guide to the NQF

- Icons legend

- Section 1: Introduction

- Section 2: Applications and Approvals

- Section 3: National Quality Standard and Assessment and Rating

- Section 4: Operational Requirements

-

Section 5: Regulatory Authority Powers

- 1. Monitoring

- 2. Compliance tools

- 3. Enforceable undertakings

- 4. Amendment of approval – Conditions

- 5. Suspensions and cancellations

- 6. Cancellation of service approval

- 7. Cancellation of provider approval

- 8. Serving notices

- 9. Publishing information about enforcement actions

- 10. Powers of regulatory authorities

- 11. Powers of authorised officers

- 12. Conducting an investigation

- 13. Offences relating to enforcement

- 14. Complaints

- 15. Good regulatory practice

- Section 6: Reviews

- Section 7: Glossary

- Guide to the NQS reference list

Need help using the guide? Visit our help section.

15. Good regulatory practice

15.1 Why are regulatory authorities regulating?

Regulatory authorities and the Australian Children’s Education and Care Quality Authority (ACECQA) are regulating to:

- further the objectives of the National Law

- influence the behaviour of providers, nominated supervisors and educators in ways that are consistent with these objectives, and improve outcomes for children

- fulfil their obligations under the National Law and Regulations.

Objectives of the National Law

The National Law’s objectives are shared by regulatory authorities and ACECQA and underpin regulatory actions and decisions.

The objectives are set out below:

- ensure the safety, health and wellbeing of children attending education and care services

- improve the educational and developmental outcomes for children attending education and care services

- promote continuous improvement in the provision of quality education and care services

- establish a system of national integration and shared responsibility between participating jurisdictions and the Commonwealth in the administration of the NQF

- improve public knowledge, and access to information, about the quality of education and care services

- reduce the regulatory and administrative burden for education and care services by enabling information to be shared between participating jurisdictions and the Commonwealth.

Best practice regulation principles

Regulatory authorities and ACECQA are guided by best practice regulation principles in the day-to-day implementation of the National Law.

The nine principles below apply to all regulatory work, from education and information giving, to investigation and enforcement.

1. Outcomes focused

Regulatory actions should not be seen as ends in themselves. They should promote improved quality outcomes for children and families, and further the objectives of the National Law.

All activities of regulatory authorities should:

- be clearly focussed on the underlying regulatory objectives

- represent the course of action(s) that is likely to achieve these objectives in the most effective and efficient manner

- be integrated and aligned, that is, they work towards common purposes and objectives

- be flexible and innovative, achieving the best regulatory outcome in the particular circumstances of each case.

Regulatory authorities should be guided by evidence and the objectives of the National Law to regularly review the effectiveness of regulatory actions.

2. Proportionality and efficiency

The design and application of regulation should be proportionate to the problem or issue it is seeking to address. Proportionality involves ensuring that regulatory measures do not ‘overreach’, or extend beyond achieving an identified objective or addressing a specific problem. The scope and nature of regulatory measures should match the benefits that may be achieved, by improving outcomes for children or families, or reducing risk of harm.

Regulatory effort should also be focussed where it will generate the greatest benefits from the resources employed. Actions should be targeted at areas where the largest gains can be made. Regulatory authorities should prioritise effort and resources to areas where, based on the available evidence, the potential benefits and risks are more significant.

3. Responsiveness and flexibility

Regulatory authorities should be responsive and flexible by:

- considering the full range of options available to them

- tailoring their approach to account for the circumstances of each individual case

- focusing on consistency of outcome

- regularly reviewing their practice and operational policy to ensure it is evidence based, remains relevant and appropriate to changes in the sector.

Regulatory authorities should be responsive to the particular circumstances of each region, location and provider. Regulatory authorities may adopt different approaches to the same or similar issues, owing to, for example, the prevalence of that issue, compliance history, the particular importance of the issue or other relevant differences across jurisdictions, or within a jurisdiction.

Regulatory authorities should encourage and not constrain appropriate and desirable innovation by education and care providers, within the bounds of regulatory requirements.

4. Transparency and accountability

Regulatory actions should be open and transparent to encourage public confidence and provide certainty and assurance for regulated entities.

Legislation should be fairly and consistently administered and enforced and, where relevant, regulatory authorities should explain the reasons for their decisions.

Regulatory authorities should also be accountable for the actions they take, and welcome public and sector scrutiny, including the regular reporting of performance information.

In general, the design and administration of regulation should provide for transparent and robust mechanisms to appeal against decisions made by regulators.

5. Independence

Regulatory authorities should ensure the integrity and objectivity of regulatory actions. Where regulatory authorities exercise powers or make decisions, this should be done in the absence of actual or perceived conflicts of interest or other relationships, measures or influences that may impinge, or be seen to impinge, upon their objectivity.

Abiding by this principle should not jeopardise having constructive working relationships between regulators and regulated entities.

6. Communication and engagement

Regulatory authorities operate in a dynamic context made up of a broad range of stakeholders, including:

- government agencies (for example, policy agencies, other regulators)

- the regulated sector (including providers, supervisors and educators)

- peak bodies

- service users (i.e. children and families)

- the broader community.

Engaging appropriately with each stakeholder group makes regulatory activities more efficient and effective, for example:

- exchanging operational information with other government agencies can inform better policy development, and mutually improve regulatory decision-making

- appropriate relationships with the regulated sector can facilitate more effective educative and advisory regulatory approaches, as well as enabling the regulator to obtain valuable feedback and information that improves its own performance

- outward communication of performance and outcomes to service users and the broader community supports better information and decision-making, as well as greater transparency and public accountability.

7. Mutual responsibility

Regulatory authorities should acknowledge the primary responsibility of education and care providers, their owners, managers and staff, for maintaining and improving the quality of their services.

Providers, supervisors and educators are responsible for meeting their obligations under the National Law and Regulations, for ensuring the safety, health and wellbeing, and improving the educational and developmental outcomes of children in their care.

The role of regulatory authorities is to administer the National Law and Regulations, promoting quality improvement through exercising the powers and functions given to them by the legislation.

8. Consistency and cooperation across jurisdictions

Cooperation and coordination between the jurisdictions is critical to ensure efficiency, consistency and predictability of regulatory systems. It can also ensure that scarce public resources are employed efficiently, reducing duplication of regulatory effort and improving effectiveness.

Central to achieving cooperation across regulatory authorities is agreement on the sharing of data and information to the greatest extent possible within the limits of the law.

Regulatory authorities should also share evidence, experimentation, experience and policy initiatives to facilitate the adoption of best practice across jurisdictions.

9. Awareness of the broader regulatory environment

Regulatory authorities should be aware of the existence of other relevant and overlapping regulatory schemes, the role these schemes perform and the obligations they impose on businesses and other organisations.

Regulatory authorities should:

- minimise the duplication of regulatory obligations, impositions and effort

- cooperate and coordinate information sharing.

For those jurisdictions where some or all preschool services are delivered through the government school system, regulatory action should be cognisant of the policy and regulatory environment in that system.

Other relevant regulatory systems could include those relating to:

- child protection

- occupational health and safety

- planning

- food safety.

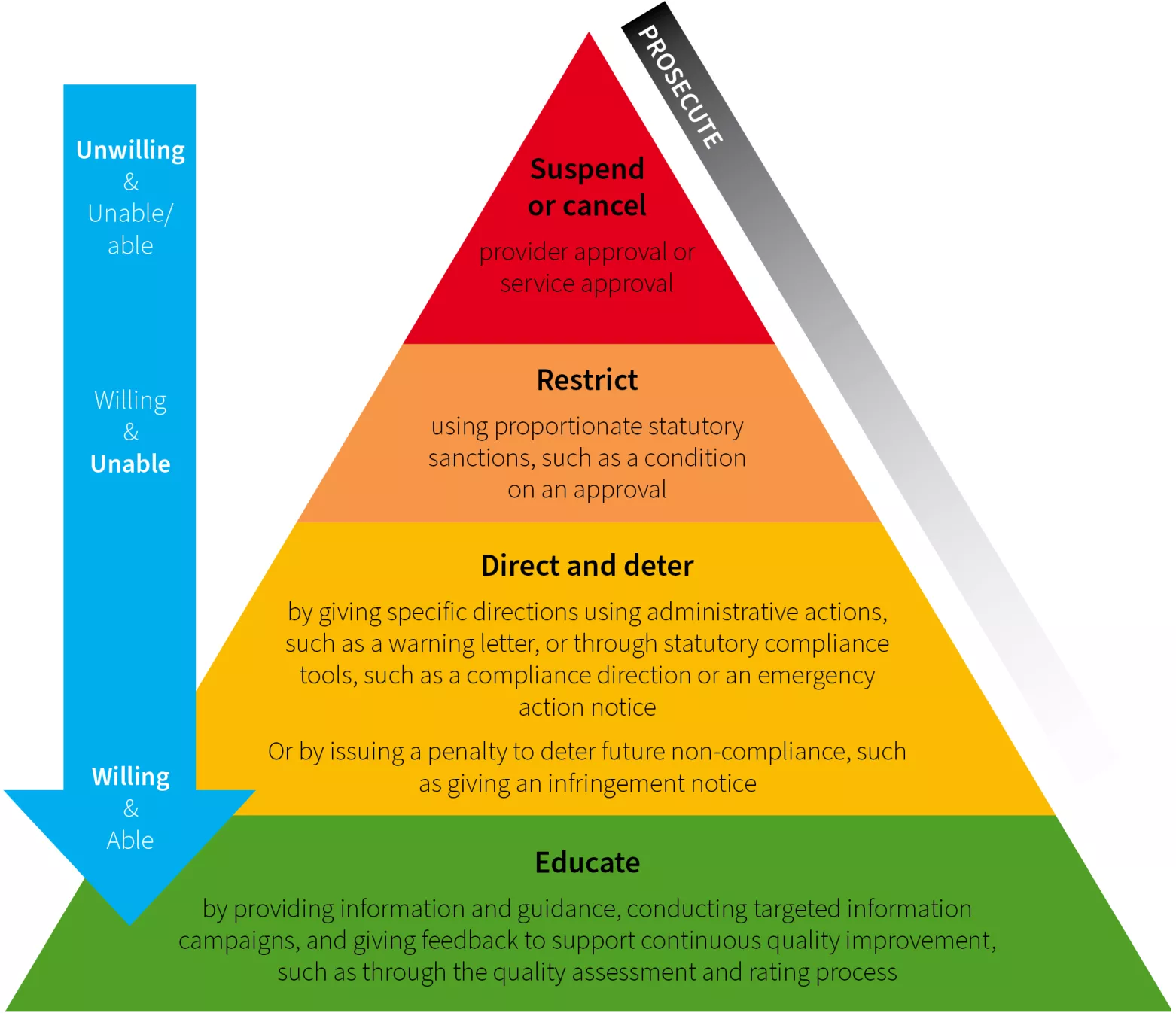

15.2 Regulatory practice diagrams

Ayres and Braithwaite enforcement pyramid

In their book, Responsive Regulation: Transcending the deregulation debate, Ian Ayres and John Braithwaite suggest a responsive compliance model. This model can be depicted as a pyramid, its shape indicating the:

- number of entities (i.e. service providers and others with liabilities under the legislation) likely to be found at each level of the model

- hierarchical and escalating nature of regulatory engagement

- increasing focus towards the top of the pyramid on the small minority of entities that appear to deliberately not comply.

The responsive compliance model is dynamic and allows versatility in managing non-compliance. The model’s strength is that it allows regulatory authorities to identify the best remedy for the particular situation. This includes taking into account an entity’s efforts to comply. Having a set of graduated responses enables the regulatory authority to:

- respond in a way that is proportionate to the risk

- escalate regulatory action

- de-escalate regulatory action

- minimise costs associated with a response.

The diagram above is adapted from a version of the regulatory compliance pyramid published in the Australian National Audit Office Better Practice Guide. The vertical arrow demonstrates the range of responses to regulation. Providers and other people with obligations under the legislation who are willing and able to respond to regulation comply most of the time. Those who are unwilling and/or unable to respond require more persuasive deterrents and remedies. The responsive compliance pyramid model is also consistent with the principle of earned autonomy, where regulatory intervention is focussed towards those who are unwilling and/or unable to comply.

Prosecutions: Bring an offence against the National Law or Regulations for decision by a court or tribunal.

Statutory sanctions: Cancellations, suspensions, conditions, infringement notices, compliance notices, compliance directions, enforceable undertakings, emergency action notices, prohibition notices, direction to exclude an inappropriate person.

Administrative actions: Additional monitoring, meetings, warning letters or cautions.

Information and guidance: Factsheets, newsletters, FAQs, helplines, campaigns, capacity-building, practice notes and guidelines.

15.3 Assessing risk to children

[ National Law, Sections 3–4 ]

When exercising functions under the National Law, regulatory authorities must consider the Law’s objectives and guiding principles. These include ensuring the safety, health and wellbeing of children attending education and care services, and improving their educational and developmental outcomes. They also include promoting continuous improvement in the provision of quality education and care services.

To fulfil this responsibility, regulatory authorities often need to assess the level of risk to children at education and care services. The guidance below is to help regulatory authorities carry out a risk assessment and determine appropriate follow up action.

What is risk?

The National Law and Regulations do not define ‘risk’. A common tool used to analyse the level of risk is a risk matrix (see below). This tool helps identify the level of risk by looking at how likely it is a negative event may occur, and the severity of the consequence should it occur.

Risk can arise:

- through any part of the environment where education and care is provided to children including the physical environment, staff members and other people at the service

- from an action or through a failure to act

- from systemic failure, such as a provider not having adequate systems in place to control for risk.

Risk Matrix |

||||||

|

Consequences |

Likelihood |

|||||

|

Rare |

Unlikely |

Possible |

Likely |

Almost Certain |

||

|

Major |

Moderate |

High |

High |

Critical |

Critical |

|

|

Significant |

Moderate |

Moderate |

High |

High |

Critical |

|

|

Moderate |

Low |

Moderate |

Moderate |

High |

High |

|

|

Minor |

Very low |

Low |

Moderate |

Moderate |

Moderate |

|

|

Insignificant |

Very low |

Very low |

Low |

Moderate |

Moderate |

|

Likelihood

The risk matrix includes five levels of likelihood, which are described below. When thinking about likelihood, regulatory authorities should take into account factors such as history of compliance, as well as readiness, willingness and ability to comply. It is also important to consider how soon an event might occur, as this will help decide the most suitable action for responding to the risk.

|

Likelihood |

Description |

|

Rare |

Very unlikely – the event may occur only in exceptional circumstances |

|

Unlikely |

Improbable – the event is not likely to occur in normal circumstances |

|

Possible |

Potential – the event could occur at some time |

|

Likely |

Probable – the event will probably occur in most circumstances |

|

Almost certain |

Very likely – the event is expected to occur in most circumstances |

Consequence

The risk matrix includes five levels of consequence: insignificant, minor, moderate, significant and major. This takes into account the impact, or potential impact, of an event including its scale and duration. A consequence might affect the safety and wellbeing of children at the service, their family or the wider community.

When analysing the consequences of a potential event, regulatory authorities should consider the vulnerability of people who might be affected. For instance, very young children or children with a disability may be particularly vulnerable, because they are less able to act to protect their wellbeing.

Harm to children might arise as the result of a single incident or from several incidents that occur over time. This is known as cumulative harm.

Risk prioritisation

A risk matrix helps work out the priority of a particular risk. This can help regulatory authorities determine which risks to address first. The priorities in the above risk matrix are: very low, low, moderate, high and critical.

Monitoring, Compliance and Enforcement has information about tools available to regulatory authorities, which can be used to compel providers to reduce risks to children.

Once the regulatory authority has taken action to compel the approved provider to reduce the risk, it can reassess the level of risk to children using the risk matrix. If it considers the risk to children is still moderate or greater, the regulatory authority should consider further options for compelling the provider’s compliance. The aim is to reduce the level of risk to very low or low. However, depending on the circumstances, regulatory authority may decide to act to address a low or very low level risk, as there may be ways of further reducing the risk or removing it entirely.

Unacceptable risk

The term ‘unacceptable risk’ appears in a number of provisions in the National Law and Regulations (see table below). The National Law and Regulations do not define ‘unacceptable risk’. This is because the nature and degree of risk to children will vary depending on the particular circumstances.

The National Law allows regulatory authorities to prevent a provider or service from operating if the regulatory authority is satisfied there is an unacceptable risk to the health, safety or wellbeing of children at the service. In the case of a prohibition notice, the regulatory authority can prevent a person from having any involvement with any service if they are satisfied there is an unacceptable risk.

The regulatory authority may consider there is an unacceptable risk if the operation of the service has resulted in harm to children, and there are no options for effectively reducing the risk to children. For example, the regulatory authority may have made previous attempts to ensure the provider reduces or eliminates risk to children, without success.

Because risk includes analysing potential consequences, the regulatory authority might also be satisfied there is an unacceptable risk to children even where no child has been harmed.

Regulatory authorities can use the risk matrix to help determine whether a risk is unacceptable. It is likely that a risk that falls into the ‘critical’ category will be unacceptable, but regulatory authorities should always use their judgement and take into account the specific circumstances when determining appropriate action.

Provisions with reference to unacceptable risk to children |

||

|

S 31 |

Grounds for cancellation of provider approval |

The regulatory authority may cancel a provider approval if it is satisfied that the continued provision of education and care services by the approved provider would constitute an unacceptable risk to the safety, health or wellbeing of any child or class of children being educated and cared for by an education and care service operated by the approved provider. See Applications and Approvals for more information on cancelling a provider approval. |

|

S 49 |

Grounds for refusal to grant service approval |

The regulatory authority must refuse to grant a service approval if it is satisfied that the service, if permitted to operate, would constitute an unacceptable risk to the safety, health or wellbeing of children who would be educated or cared for by the education and care service. See Applications and Approvals for more information on refusing to grant a service approval. |

|

S 77 |

Grounds for cancellation of service approval |

A regulatory authority may cancel a service approval if it reasonably believes that the continued operation of the education and care service would constitute an unacceptable risk to the safety, health or wellbeing of any child or class of children being educated and cared for by the education and care service. See Applications and Approvals for more information on cancelling a service approval. |

|

S 182 |

Grounds for giving prohibition notice |

The regulatory authority may give a prohibition notice to a person who is in any way involved in the provision of an approved education and care service if it considers that there may be an unacceptable risk of harm to a child or children if the person were allowed to remain on the education and care service premises or to provide education and care to children. See Monitoring, Compliance and Enforcement for more information on issuing a prohibition notice. |

|

R 25 |

Additional information about proposed education and care service premises |

An application for a service approval for a centre-based service must include a statement made by the applicant that states that, to the best of the applicant’s knowledge the site history does not indicate that the site is likely to be contaminated in a way that poses an unacceptable risk to the health of children. See Applications and Approvals for more information on service approval applications. |

15.4 Good decision-making

Good decision-making refers to the lawful and proper exercise of public power. Public power is the power vested in government agencies to make decisions which impact on the rights, interests and legitimate expectations of individuals. Administrative law regulates the exercise of public power by defining the extent of the power and by giving individuals the right to challenge decisions made by government.

Preparing to make the decision

Before making a decision, decision-makers must ensure they have prepared appropriately. This involves identifying and recording key issues, creating and maintaining a document trail, checking any legal requirements and identifying the limits of the available decision-making power.

Checking delegation

Decision-makers must check they are authorised to make the decision. If the decision-maker does not have the power to make the decision, the decision may not be lawful. If the law does not give the decision-maker the power to make the decision themselves, they need to check if this power has been delegated to them. When a person with the authority to make a decision passes the power to someone else, it is called a delegation. Delegations are often specific to a position and are generally outlined in an operational document.

Authorised officers should check which decisions they are authorised to make and be aware that sometimes the authority to make a decision will rest with someone else within the regulatory authority.

The person with the authority to make the decision is responsible for ensuring the decision is made properly.

Power under the law

The power to make a decision, and the limits on that power, are set by acts of parliament (for example the National Law), associated instruments (for example the National Regulations) and case law (law made by courts).

For example, the National Law sets out the types of decisions regulatory authorities can make about applications for provider or service approval, or for an amendment to, or suspension of, an approval.

Guidelines and policies

Government agencies, generally, have guidelines and policies to help guide decision-makers. However, decision-makers must remember that policy cannot override the law. Although relevant policy should be considered when making a decision, policy must be applied reasonably and consistently with the law. Decision-makers must not make a decision without considering the merits of the particular case.

Timeframes

When a timeframe for making a decision is included in the legislation, for example, ‘30 days after receiving an application’, these timeframes must be adhered to. The National Law specifies that for provider and service approval applications, failing to make a decision within the set timeframe, including timeframes extended under the legislation, will automatically result in a ‘deemed refusal’ of the application.

A deemed refusal gives the applicant the right to apply for a review as if the regulatory authority had made a decision to refuse the application. Where a regulatory authority is aware that it will not meet (or is not likely to meet) the timeframe set out in the legislation, it should notify the applicant and, wherever possible, give an indication of when the decision will be made.

For applications without a ‘deemed refusal’ provision, if the regulatory authority does not make a decision within the legislated timeframe, an applicant may follow up the decision in a range of ways, including by involving the relevant ombudsman. In any case, best practice is to inform applicants of any delays or potential delays in deciding an application.

Considering the decision

Decision-makers must consider all relevant documents and information to ensure a fair and informed decision. They must not take any irrelevant documents or information into account.

Decision-makers must ensure they have fully considered all available evidence, particularly when the decision-maker did not personally collect the evidence.

The National Law sets out what the regulatory authority must consider when deciding an application and, generally, does not limit the regulatory authority from considering any other relevant matter.

To ensure accountability and transparency, decision-makers should always maintain accurate and complete records of the information that informs their decision.

Natural justice

The terms ‘natural justice’ and ‘procedural fairness’ are often used interchangeably.

Natural justice means that any person who may be affected by the decision is given a chance to a fair hearing, with full knowledge of their rights and responsibilities, before a decision is made.

Natural justice must be given when the rights, interests or legitimate expectations of individuals may be affected by the exercise of power (i.e. when a decision may not be in favour of the person). However, it is best practice to always give natural justice even when a decision may appear to be in favour of an affected person.

Natural justice has three main elements:

- the notice requirement

- the hearing rule

- the bias rule.

The notice requirement

A person affected by the decision must be notified of any issues in enough detail to allow them to participate or respond in a meaningful way. This may require the decision-maker to present the person with material that may be unfavourable to them.

The National Law includes a number of ‘show cause’ provisions that underline the principles of natural justice. ‘Show cause’ provisions aim to ensure affected individuals are aware of the decision-maker’s intention, the reasons why the decision-maker is considering making the decision, and give an opportunity to respond.

‘Show cause’ provisions apply to prohibition notices and the suspension or cancellation of provider and service approvals.

A ‘show cause’ provision also applies to the suspension of education and care by a family day care educator. However, this ‘show cause’ provision is discretionary. Regulatory authorities should still consider natural justice obligations, despite the discretion.

The hearing rule

Decision-makers must provide any affected person with a reasonable opportunity to respond to material provided by the decision-maker. The hearing rule ensures the decision-maker has taken any responses into account in making the decision. The hearing rule does not require a formal ‘hearing’ – the affected person could be provided with an opportunity to respond in writing.

The bias rule

Decision-makers must act impartially and not in their own interests. To maintain public confidence in the integrity of the system, the rule also requires that the decision-maker is not perceived as being biased.

Bias may arise from a conflict of interest or from the impression that the decision-maker has made a judgment on the issue without considering all relevant factors or by considering irrelevant factors.

While a conflict of interest does not always demonstrate a decision-maker’s inability to make an impartial judgment, it is generally considered best practice to employ a different decision-maker to avoid the perception of bias.

Making the decision

Once the relevant information and documents have been collected and all affected people have been afforded natural justice, decision-makers need to establish the facts. In establishing the facts, decision-makers must consider all available evidence before deciding which facts are relevant to the decision and which should be discarded due to irrelevance. It is crucial that decision-makers establish facts based on clear evidence.

Decision-makers can consult with other officers and refer to policies and guidelines to help them make a decision, but they must act independently, not at the direction of others, when making a decision. See Reviews for more information about best practice decision-making when conducting reviews.

After determining the relevant facts, the decision-maker must apply the relevant legislation to the facts. Where there is uncertainty about the interpretation of the law, the decision-maker should take into account the objectives and purpose of the legislation. Decisions made under the National Law should consider the objectives and guiding principles.

When a decision is made under a power granted by legislation, it is important that the relevant legislation is correctly interpreted and applied. If the decision-maker is in doubt about the interpretation, they should seek legal advice.

Once the decision is made, the decision and all supporting evidence should be kept on record. The decision-maker should also document all matters that were taken into account when making the decision. Decision records must generally include the information outlined below, and should be accompanied by a statement of reasons explaining the decision.

Explaining, recording and communicating the decision

Decisions in the public sector are recorded in a variety of ways. The record of a decision must be a standalone record that can be read without reference to a file and should include the following information:

- the date

- who the decision is about

- what the decision is

- who the decision-maker is

- the signature of the decision-maker.

A statement of reasons isn’t always required for a decision, however, an affected person may request reasons; sometimes a long time after the decision has been made. For this reason, it is best practice to record a statement of reasons at the time the decision is made.

Individuals may access information, including decision-making documentation, from government agencies under Privacy and Freedom of Information legislation.

A statement of reasons should be clear, unambiguous, jargon-free and easily read and understood by the affected persons.

Generally, statements of reasons should include the following information:

- the decision-maker’s findings on the facts

- reference to, or copies of, documents, evidence and relevant information considered in making the decision

- a meaningful statement of reasons addressing all the critical issues and any adopted recommendations, clearly explaining the decision-maker’s understanding and application of the law

- the identified grounds for review.