BELONGING, BEING & BECOMING - THE EARLY YEARS LEARNING FRAMEWORK

Belonging, Being and Becoming: The Early Years Learning Framework for Australia (EYLF) is the national approved learning framework under the NQF for young children from birth to 5 years of age.

| We acknowledge the Traditional Owners and Custodians of the Lands across Australia. We also acknowledge and extend our respect to Elders, past and present. We recognise and celebrate the contributions of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the First Peoples of Australia, including their role in the education and care of children. We also acknowledge and recognise the rich histories and diverse cultures of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, and the valuable contribution their diversity brings. |

|---|

(EYLF) INTRODUCTION

This is V2.0 of Australia’s national Early Years Learning Framework. The aim of Belonging, Being and Becoming: The Early Years Framework for Australia is to support early childhood providers, teachers and educators to extend and enrich children’s learning from birth to 5 years and through the transition to school. The Early Years Learning Framework (the Framework) draws on robust Australian and international evidence that confirms early childhood is a vital period in children’s continuing learning, development and wellbeing. It has been developed with considerable input from the early childhood sector, including children and families, approved providers and educators, other professionals, peak bodies, early childhood researchers, as well as the Australian and state and territory governments and the Australian Children’s Education and Care Quality Authority.

The Human Rights Commission describes Australia as a vibrant, multicultural country. “We are home to the world’s oldest continuous cultures, as well as Australians who identify with more than 270 ancestries” (Australian Human Rights Commission, 2019).

In recognition of this, and the guiding principles of the National Quality Framework, the Early Years Learning Framework contributes to the realisation of Goal 1 and 2 of the Alice Springs (Mparntwe) Education Declaration (Education Council 2019 p. 4) that:

Goal 1: The Australian education system promotes excellence and equity. Goal 2: All young Australians become:

|

|---|

The Alice Springs (Mparntwe) Education Declaration commits governments to ensuring all children learn about the diversity of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures, and to seeing all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children thrive in their education and all facets of life. Contributing to this goal, the National Agreement on Closing the Gap, led by the Coalition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Organisations and all Australian governments, identifies early childhood education, care and development as a national policy priority. Furthermore, it commits to ensuring all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children are engaged in high quality, culturally appropriate early childhood education in their early years. Early childhood education has a critical role to play in delivering this outcome and advancing Reconciliation in Australia.

As part of the National Quality Framework, the Early Years Learning Framework supports the objectives and principles of the National Law and Regulations including the National Quality Standard. Recognising children as competent and capable learners who have rights and agency, the Framework has a specific emphasis on play-based learning and the intentional role played by both educators and children in extending and enriching learning. The Framework identifies a shared Vision for children’s learning, Principles and Practices to underpin learning and teaching and the 5 Learning Outcomes. Together these elements inform the professional work of early childhood teachers and educators. The Framework has been designed for use by early childhood educators, early childhood teachers1 and approved providers working in partnership with children, families, other professionals, schools and community members to inform educational programs and practices that are place-based and relevant to that community.

Educators guided by the Framework will reinforce in their daily practice the principles laid out in the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (the Convention) (United Nations 1989). The Convention states that all children have the right to an education that lays a foundation for the rest of their lives, maximises their ability, and respects their family, cultural and other identities and languages. The Convention also recognises children’s right to play and be active participants in all matters affecting their lives. Underpinned by a child-rights approach, the Framework supports implementation of the National Principles for Child Safe Organisations (Australian Human Rights Commission 2018). It also promotes children’s safety, wellbeing and responsibilities as active citizens.

This document may complement or supplement individual state and territory frameworks. The exact relationship will be determined by each jurisdiction. Over time additional resources may be developed to support the application of this Framework.

1 Early childhood teachers and educators are early childhood professionals who work directly with children in early childhood settings and from now on will be referred to as educators.

(EYLF) A VISION FOR CHILDREN'S LEARNING

| A vision: All children engage in learning that promotes confident and creative individuals and successful lifelong learners. All children are active and informed members of their communities with knowledge of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander perspectives. |

|---|

Fundamental to the Framework is a view of children’s lives as characterised by belonging, being and becoming. From before birth children are connected to family, communities, culture and place.

Their earliest learning, development and wellbeing takes place through these relationships, particularly within families, who are children’s first and most influential educators. As children participate in everyday life, they construct their own identities and understandings of the world. Educators engage children in learning that promotes confidence, creativity and enables active citizenship. They celebrate diversity with children and their families, and the opportunities diversity brings to know more about the world. Educators understand children may come from diverse backgrounds and acknowledge this in each child’s Belonging, Being and Becoming.

(EYLF) Belonging

Experiencing belonging – knowing where and with whom you belong – is integral to human existence. Children belong to diverse families, neighbourhoods, local and global communities. Belonging acknowledges children’s interdependence with others and the basis of relationships in defining identities. In early childhood, and throughout life, trusting relationships and affirming experiences are crucial to a sense of belonging. Belonging is central to being and becoming in that it shapes who children are and who they can become.

(EYLF) Being

Childhood is a time to be, to seek and make meaning of the world. Being recognises the significance of the present, as well as the past in children’s lives. It is about children knowing themselves, developing their identity, building and maintaining relationships with others, engaging with life’s joys and complexities, and meeting challenges in everyday life. The early childhood years are not solely preparation for the future but also about children being in the here and now.

(EYLF) Becoming

Children’s identities, knowledge, understandings, dispositions, capabilities, skills and relationships change during childhood. They are shaped by different events and circumstances. Becoming reflects this process of rapid and significant change that occurs in the early years as children learn and grow. It emphasises the collaboration of educators, families and children to support and enhance children’s connections and capabilities, and for children to actively participate as citizens.

The Framework conveys the highest expectations for all children’s learning, development and wellbeing from birth to 5 years and through the transitions to school. It communicates these expectations through the following 5 Learning Outcomes:

- Children have a strong sense of identity

- Children are connected with and contribute to their world

- Children have a strong sense of wellbeing

- Children are confident and involved learners

- Children are effective communicators.

The Framework provides broad direction for early childhood educators to facilitate all children’s learning, development and wellbeing and ensure children are supported, celebrated, and connected to their community. It guides educators in their professional decision-making and assists in planning, implementing and evaluating high quality educational programs and practices in early childhood settings. It also underpins the implementation of relational and place-based pedagogies and curriculum relevant to each local community and all children in the early childhood setting. Relational pedagogy underpins the ways in which educators build trusting, respectful relationships between children, families, other educators and professionals, as well as members of the community. Place-based pedagogy refers to an understanding that educators’ knowledge of the setting or context will influence how educators plan and practice.

The Framework is designed to inspire conversations, improve communication and provide a common language about children’s learning among children themselves, their families, the broader community, educators, teachers in schools and other professionals including those who work in child and family services, higher education and training organisations.

(EYLF) Elements of the Framework

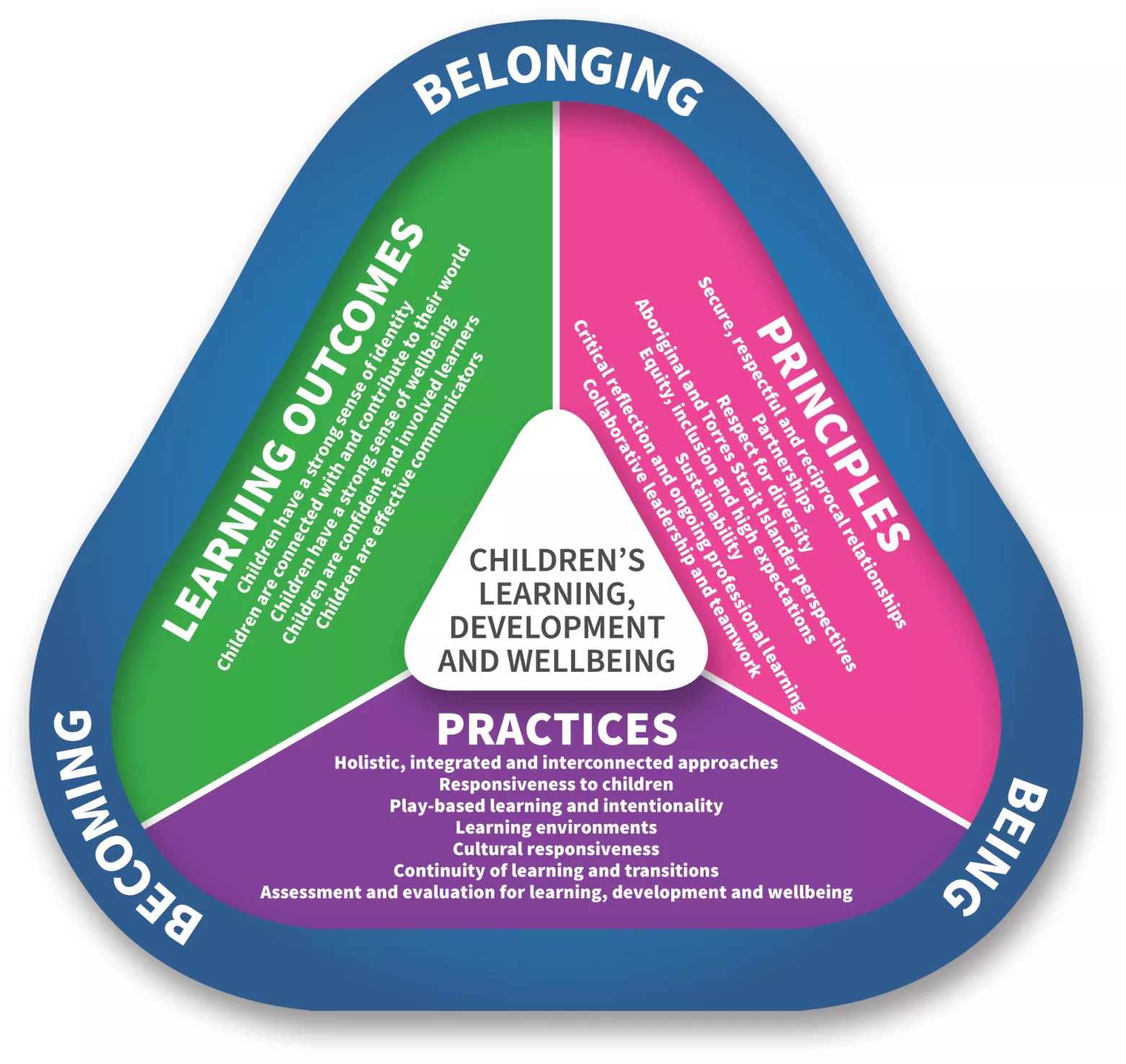

The Framework puts children’s learning at the core and comprises interdependent elements: Vision, Principles, Practices and Learning Outcomes (see Diagram 1). All elements are fundamental to early childhood pedagogy and effective curriculum decision-making.

Curriculum encompasses all the interactions, experiences, routines and events, planned and unplanned, that occur in an environment designed to foster children’s learning, development and wellbeing.

Children are receptive to a wide range of experiences. What is included or excluded from the curriculum affects how children learn, develop and understand the world.

The Framework supports curriculum decision-making as a continuous cycle of planning, assessment and critical reflection. This involves educators knowing the children, families and community contexts and drawing on their professional knowledge to plan for individual children and groups. These plans are implemented, evaluated and reflected upon to inform further planning.

Working in partnership with children and families, and communities, teachers in schools, and other professionals, educators use the Vision, Principles, Practices and Learning Outcomes to guide their planning for children’s learning, development and wellbeing. To actively engage children, educators identify children’s strengths, choose appropriate teaching strategies and content, design the learning environment, and collaborate with children to co-construct learning. Educators build an engaging child-centred curriculum when they plan, analyse and assess children’s learning and critically reflect and evaluate planning and practice for and with children.

(EYLF) Children’s learning

The diversity in family and community life in Australia means that children experience belonging, being and becoming in many ways. They bring their diverse experiences, home languages, perspectives, expectations, and cultural ways of knowing, being and doing to their learning.

Children’s learning is dynamic, complex and holistic. This means that cognitive, linguistic, physical, social, emotional, personal, spiritual and creative aspects of learning are all intricately interwoven and interrelated.

Play-based learning capitalises on children’s natural inclination to be curious, explore and learn. Children actively construct their own understandings that contribute to their own learning. In play experiences children integrate their emotions, thinking and motivation that assists to strengthen brain functioning. They exercise their agency, intentionality, capacity to initiate and lead learning, and their right to participate in decisions that affect them, including about their learning.

Play-based learning:

- allows for the expression of personality and uniqueness

- offers opportunities for multimodal play

- enhances thinking skills and lifelong learning dispositions such as curiosity, persistence and creativity

- enables children to make connections between prior experiences and new learning and to transfer learning from one experience to another

- assists children to develop and build relationships and friendships

- develops knowledge acquisition and concepts in authentic contexts

- builds a sense of identity

- strengthens self-regulation, and physical and mental wellbeing.

Viewing children as active participants and decision-makers opens possibilities for educators to move beyond preconceived expectations about what children can do and learn. This requires educators to understand, respect and work with each child’s unique qualities and capabilities.

Educators’ practices and the relationships they form with children and their families have a significant effect on children’s participation in early childhood education, engagement in learning opportunities and success as learners. Children thrive when they, their families and their educators work together in partnership to support their learning, development and wellbeing. Relationships are strengthened when educators recognise and affirm children’s home languages and cultural identities and when they create culturally secure and safe places for children and their families.

Children’s early learning influences their continuing educational journeys. Wellbeing and a strong sense of connection, optimism, resilience and engagement enable children to develop a growth mindset, and a positive attitude to learning.

The Learning Outcomes section of the Framework provides examples of evidence of children’s learning, development and wellbeing, and the educator’s intentional role in extending and enriching children’s play, thinking, learning and sense of wellbeing.

(EYLF) ELEMENTS OF THE EARLY YEARS LEARNING FRAMEWORK

Diagram 1

This diagram shows the integrated connections of the Vision, Principles, Practices and Learning Outcomes that centre on children’s learning, development and wellbeing. Belonging, Being and Becoming overlap all these elements.

(EYLF) EARLY CHILDHOOD PEDAGOGY

The term pedagogy in this Framework refers to the art, science or craft of educating. It describes the professional knowledge, practices and creativity that educators use to intentionally foster and nurture children’s learning, development and wellbeing. When educators establish respectful relationships with children and their families, they are able to work together to use relational and place-based pedagogies that assist in developing curriculum relevant to children in their local context. Using these pedagogies and other child-centred approaches supports curriculum decisions that include children’s ideas and reflect their curiosity, allowing them to celebrate their own interests, friendships and express themselves in different ways.

Educators’ professional judgements are central to their active role in facilitating children’s learning. In making professional judgements, they intentionally weave together their:

- professional knowledge and skills

- contextual knowledge of each child, their families and communities

- understanding that relationships with children and families are critical to creating safe and trusting spaces

- awareness of how their beliefs and values impact children’s learning and wellbeing

- knowledge and understanding of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander perspectives

- personal styles and past professional experiences

- use of all components in the planning cycle.

Alongside their professional knowledge educators draw on their creativity, intuition and imagination, including engaging in critical reflection to evaluate and adjust their practice to suit the learners, the time, place and context of learning

(EYLF) EARLY CHILDHOOD PEDAGOGY cont.

Different theories, world views and knowledges inform early childhood approaches and practices to promote children’s learning, development and wellbeing. Educators draw upon a range of perspectives in their work which may include:

- developmental theories that focus on describing and understanding the influences on, and processes of children’s learning, development and wellbeing over time. For example, attachment theory explains children’s formation of trusting relationships with important adults; social learning theory focuses on how children observe and imitate the behaviour of others; cognitive theory describes thought processes and how this influences the ways children engage with and understand their world

- socio-cultural theories that emphasise the central role that families and cultural groups play in children’s learning and the importance of respectful relationships, and provide insight into social and cultural contexts of learning and development

- practice theories, such as affordance theory that asks educators to think, for example, about the possibilities for activity that the physical environment offers children. The theory of practice architectures invites educators to think about their sayings (understandings of their practice), their doings (the ways in which they practice) and their relatings (how they relate to others in their practice)

- ancestral knowledges are ways of knowing and understanding shared through history and culture, in the written, oral and spiritual traditions of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples

- place-based sciences that foster community connections in ways that build on local (children, families, communities and educators) funds of knowledge (experiences and understandings) that assist in building thriving learners and communities

- critical theories that invite educators to challenge assumptions about curriculum, and consider how their decisions may affect children differently

- feminist and post-structuralist theories that offer insights into issues of power, equity and social justice in early childhood settings.

Drawing on a range of perspectives and theories can challenge traditional ways of seeing children, teaching and learning, and encourage educators, as individuals and with colleagues, to:

- investigate why they act in the ways that they do

- discuss and debate theories and other perspectives to identify strengths and limitations

- recognise how theories, world views and other knowledges assist in making sense of their work, but can also limit their actions and thoughts

- consider the voices of children, their families and their communities in their decision-making

- consider the consequences of their actions for children’s experiences

- consider who is included and who is excluded or silenced by ways of working

- find new ways of working fairly, justly and inclusively

- consider the ecosystems in which children live and learn.

(EYLF) PRINCIPLES

The following 8 Principles reflect contemporary theories, perspectives and research evidence concerning children’s learning and early childhood pedagogy. The Principles underpin practice that is focused on assisting all children to make progress in relation to the Learning Outcomes. Educators consider ethical, socially just and inclusive principles for children’s learning in the early years when they:

- build secure, respectful and reciprocal relationships

- develop partnerships

- are respectful of diversity

- embed Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander perspectives

- commit to equity, inclusion and high expectations

- consider sustainability in all its forms

- engage in critical reflection and professional learning

- exercise collaborative leadership and work as a team.

(EYLF) Secure, respectful and reciprocal relationships

Educators who are attuned to children’s thoughts and feelings, support their learning, development and wellbeing. Children’s first attachments within their families and trusting relationships within other familiar settings provide them with a secure base from which to explore the environment and build new relationships. Children’s experience of positive caring relationships and interactions with others plays a crucial role in healthy brain development.

Research has shown the importance of relational and place-based pedagogies for children’s optimal learning, development and wellbeing. Through a widening network of secure relationships, children develop confidence and feel safe, respected and valued. They become increasingly able to recognise and respect the feelings of others and to interact positively with them.

Educators who prioritise nurturing relationships through culturally safe and responsive interactions, provide children with consistent emotional support. They value the role of familiar routines and everyday rituals in children’s lives, and ensure children develop the abilities and skills, such as self-regulation, and understandings they require for interacting with others. Educators also help children learn about their responsibilities to others, to support their own and others’ wellbeing, to appreciate their connectedness and interdependence as learners, and to value collaboration and teamwork.

(EYLF) Partnerships

Partnerships are based on the foundations of respecting each other’s perspectives, expectations and values, and building on the strength of each other’s knowledge and skills. Learning Outcomes are most likely to be achieved when educators work in partnership with children, families, other professionals and communities, including schools.

These partnerships recognise the diversity of families and children. In genuine partnerships, educators collaborate with children, families, other professionals, community members and teachers in schools to support children’s learning, development and wellbeing. In genuine partnerships educators:

- value and respect each other’s knowledge of each child

- value and respect each other’s contributions to and roles in each child’s life

- build trust in each other

- act with empathy and sensitivity when children are experiencing adversity

- learn about other ways of knowing, being, doing and thinking

- communicate and share information safely and respectfully with each other

- share insights and perspectives about each child with families

- acknowledge the diversity of families and their aspirations for their children

- engage in shared decision-making to support children’s learning, development and wellbeing.

Educators recognise that families are children’s first and most influential teachers. They create a welcoming and culturally safe environment where all children and families are respected regardless of background, ethnicity, languages spoken, religion, family makeup or gender. Educators, children and families collaborate in curriculum decisions to ensure that learning experiences are meaningful. Educators actively encourage such collaborations.

Ethical partnerships are formed when information is shared responsibly, and educators take safety precautions to ensure children’s right to privacy and protection. Educators know children engage with popular culture, media and digital technologies so they build partnerships with families and others to keep children safe and families aware of e-safety information.

Knowing that some children may not have experienced safe and supportive family environments, educators enact trauma informed practices. In doing so they engage with other professionals to enhance the learning, development and wellbeing of these children and as part of this educators engage in information sharing and record keeping.

Partnerships involve educators, families, other professionals, community members and teachers in schools working together for the best interests of children. These partnerships provide opportunities to explore the learning potential in everyday rituals, routines, transitions and play experiences to ensure active participation and engagement in learning is inclusive of children with diverse backgrounds, family structures and capabilities

(EYLF) Respect for diversity

There are many ways of living, being and of knowing. Children are born belonging to a culture, which is not only influenced by traditional practices, heritage and ancestral knowledge, but also by the experiences, values and beliefs of individual families and communities. Respecting diversity means valuing and reflecting the practices, values and beliefs of families within the curriculum. Educators acknowledge the histories, cultures, languages, traditions, religions, spiritual beliefs, child rearing practices and lifestyle choices of families. They build culturally safe and secure environments for all children and their families. Educators value children’s unique and diverse capacities and capabilities and respect families’ home lives.

Educators recognise that diversity contributes to the richness of our society and provides a valid evidence base about ways of knowing. For Australian children it also includes promoting greater understanding of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ways of knowing and being and actively working towards Reconciliation.

When educators respect the diversity of families and communities, and the aspirations they hold for their children, they can foster children’s motivation to learn and reinforce their sense of themselves as competent learners. They make curriculum decisions that uphold all children’s rights to have their cultures, identities, languages, capabilities and strengths acknowledged and valued, and respond to the complexity of children’s and families’ lives. Educators think critically about opportunities and dilemmas that can arise from diversity and take action to redress unfairness. They provide opportunities for children to learn about similarities and difference and about interdependence and citizenship.

(EYLF) Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander perspectives

Providing opportunities for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children to see themselves, their identities and cultures reflected in their environment is important for growing a strong identity. Embedding Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander perspectives in all educators’ philosophy and practice is a key tool to advance Reconciliation. This also contributes to Closing the Gap commitments and fulfilling every Australian child’s right to know about Australia’s First Nations’ histories, knowledge systems, cultures and languages. Embedding Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander perspectives is a shared responsibility of approved providers, educators, and other professionals working in early childhood educational settings, regardless of whether Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children and families are enrolled in that setting.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are the longest surviving Indigenous culture in the world and the custodians of this land. Their knowledge systems, traditions, ceremonies, lore and culture have survived for over 60,000 years. Relationships and continual connections to Country and community are at the heart of who they are and the contributions of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people – past and present – should be acknowledged and valued in children’s learning.

Educators think deeply and seek assistance where possible, through engaging with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, about how to embed Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander perspectives in the philosophy of the setting, their planning and implementation of curriculum. They have a responsibility to create culturally safe places, working in intercultural ways through pedagogy and practice. An intercultural space is created when educators seek out ways in which Western and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander knowledge systems work side by side.

Educators grow their knowledge of kinship systems and cultural connections in their local communities so they can build engaging reciprocal relationships between early childhood settings and community. Acknowledging the strengths and capabilities of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families while supporting wellbeing assists in reinforcing and affirming a positive sense of identity for their children.

The history and culture of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples is respectfully and truthfully reflected through community involvement and culturally sensitive practices. Embedding Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander knowledges and perspectives encourages openness to diverse perspectives, enhances all children’s experiences and assists in the authentic advancement of Reconciliation. It is a commitment to children learning about what has come before and working together for what is to come.

(EYLF) Equity, inclusion and high expectations

Educators who are committed to equity recognise that all children have the right to participate in inclusive early childhood settings, regardless of their circumstances, strengths, gender, capabilities or diverse ways of doing and being. They create inclusive learning environments and adopt flexible and informed practices, including making reasonable adjustments to optimise access, participation and engagement in learning. This supports wellbeing and positive outcomes for children in all their diversities. Reasonable adjustments2 are the measures or actions taken by approved providers and educators to assist the meaningful participation of children with disabilities or who are experiencing barriers to learning. Educators nurture children’s optimism, happiness and sense of fun and support children’s friendships and interactions with each other.

Educators engage in critical reflection, challenge practices that contribute to inequities or discrimination and make curriculum decisions that promote genuine participation and inclusion. To support all children’s inclusion, they recognise and respond to barriers that some children face, including attitudinal and practical barriers. Such barriers can be related to disability, family diversity, cultural and linguistic diversity, neurodiversity, and children and families living through trauma and adversity.

Educators view all children as competent and capable and hold high expectations for their learning. They strive to provide all children with equitable and participatory environments and experiences to promote their learning, development and wellbeing. In doing this, educators recognise that equitable means fair, not equal or the same, and some children may need greater access to resources and support to participate in early childhood settings. By developing their professional knowledge and skills, and working in partnership with children, families, communities and other professionals, educators continually strive to find equitable and effective ways to ensure that all children have opportunities to achieve Learning Outcomes and flourish.

2 Disability Standards for Education 2005 (Cth) s. 3 (Austl.).

(EYLF) Sustainability

Humanity and the planet we share with all living things face some big challenges. Educators and children have important and active roles to play in creating and promoting sustainable communities. Broadly defined, sustainability spans environmental, social, and economic dimensions which are intertwined. Environmental sustainability focuses on caring for our natural world and protecting, preserving and improving the environment. Social sustainability is about inclusion and living peacefully, fairly and respectfully together in resilient local and global communities. Economic sustainability refers to practices that support economic development without negatively impacting the other dimensions. This includes a focus on fair and equitable access to resources, conserving resources, and reducing consumption and waste.

Adopting this broader definition helps to meet the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. In sustainable communities, the requirements of humans, animals, plants, lands, and waters can be met now and for generations to come.

Educators recognise children’s avid interest in their world, their ability to engage with concepts of sustainability and their capacity to advocate and act for positive change. Children’s agency and their right to be active participants in all matters affecting their lives is supported. Further, children’s understanding of their citizenship, and rights and responsibilities as members of local and global communities, is built through meaningful and relevant educational experiences.

Thinking about sustainability means thinking about the future and acting to create healthy, just and vibrant futures for all. Educators encourage children to develop appreciation of the natural world, understand our impact on the natural world, and the interdependence between people, animals, plants, lands and waters. Sustainable practices are created with children and children are supported to take an active role in caring for the environment and to think about ways they can contribute to a sustainable future. Recognising that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have looked after Country for the past 60,000 years, educators and children learn about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander history, culture and rich sustainable practices.

Educators provide opportunities for children to learn about all the interconnected dimensions of sustainability, understanding that sustainability goes beyond learning in nature and being involved in nature conservation. Children are supported to appreciate that sustainability embraces social and economic sustainability – as well as environmental sustainability – and to engage with concepts of social justice, fairness, sharing, democracy and citizenship

(EYLF) Critical reflection and ongoing professional learning

Educators continually seek ways to build their professional knowledge and skills and develop learning communities. They are co-learners with children, families and community, and value the continuity and richness of local knowledge shared by community members, including Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Elders. Reflection and critical reflection are 2 terms that are often used interchangeably but are different practices.

Reflection involves educators thinking intentionally about their own and others’ practices, with certain aims or goals in mind. Critical reflection is a meaning-making process that involves a deeper level of thinking and evaluation. It requires engagement with diverse perspectives such as philosophy, theory, ethics and practice and then evaluating these in context, leading to pedagogical decisions and actions that are transformative. As professionals, educators collaboratively explore, identify and evaluate diverse perspectives with respect to their own settings and contexts. In this way, critical reflection informs future practice in ways that demonstrate an understanding of each child’s learning, development and wellbeing, and have implications for equity and social justice.

In practice, educators can frame their critical reflection within a set of overarching questions, developing more specific questions for areas of inquiry. Overarching questions to guide critical reflection might include:

- What is our understanding of each child, their culture and context?

- What questions do we have about our work? What are we challenged by? What are we curious about? What are we confronted by in relation to our own biases?

- What theories, philosophies and understandings shape and assist our work?

- In what ways – if any – are the theories, knowledges and world views that we usually draw on to make sense of what we do limiting our practice?

- What other theories or knowledge and world views could help us make sense of what we have observed or experienced? What are they? How might those theories and that knowledge affect our practice?

- Who is advantaged/included when we work in this way? Who is disadvantaged, excluded or silenced?

A robust culture of critical reflection is established when educators as a team, as well as children and families, are all involved in an ongoing cycle of review. Current practices are examined, outcomes of those practices evaluated, new ideas generated, tried and tested. This approach supports educators to question established practices and to think about why they are working in particular ways. In such a climate, there is opportunity to engage in deep thinking about pedagogy, equity and children’s wellbeing. Educators who are critically reflective are also committed to their own ongoing professional learning and development, actively seeking out opportunities that develop capabilities, as well as collaborating with their colleagues on aspects of practice in the early childhood setting.

As professionals, educators are committed to lifelong learning and seek out opportunities to strengthen their professional knowledge and skills to support continuous quality improvement in practice. Working in collaboration with colleagues, they identify and negotiate learning priorities, reflect on how they learn best, and look for evidence-informed learning experiences that support deep learning, critical reflection and practice change. Educators recognise that ongoing learning can take many forms. This may include professional learning experiences within settings, for example, professional conversations within teams, coaching and mentoring, professional reading, practitioner inquiry and participating in collaborative research projects. It may also include learning opportunities offered by others, for example, pursuing further study, attending professional conferences and completing professional learning programs. Within early childhood settings, team members share new knowledge and skills gained through professional learning experiences and encourage and support the ongoing learning of others.

(EYLF) Collaborative leadership and teamwork

All educators exercise aspects of leadership in their daily work with children, families and colleagues. Educators lead their own ethical practice as they take professional and personal responsibility for their actions and the decisions they make. Collaborative leadership and teamwork are built on a sense of shared responsibility and professional accountability for children’s learning, development and wellbeing. It is a view of leadership that empowers all members of the team to use their professional knowledge and skills in ways that assist everyone to do the best they can for children, families and colleagues in their setting.

Collaborative leadership and teamwork are aspects of a positive work culture where a motivation to enact a professional philosophy of cooperation and collaboration enables positive relationships to grow. Children and families are attuned to the work culture of an early childhood setting, which influences their relationships, interactions and experiences within that setting.

Collaborative leadership and teamwork are built on professional and respectful conversations about practice. Educators engage with different ways of thinking and working to critically reflect on their practice both individually and as a team, and contribute to curriculum decisions and quality improvement plans. Children’s learning, development and wellbeing is optimised when educators communicate and share ideas and views about improving practice. Collaborative leadership and teamwork support a culture of peer mentoring and shared learning where all team members contribute to each other’s professional learning and growth for high quality programs for children in early childhood settings

(EYLF) PRACTICES

The Principles of early childhood pedagogy underpin practice. Educators draw on a rich repertoire of pedagogical practices to inform curriculum for children’s learning, development and wellbeing by:

- adopting holistic approaches

- being responsive to children

- planning and implementing play-based learning with intentionality

- creating physical, temporal, intellectual, social and emotional environments

- valuing the cultural and social contexts of children and their families

- providing for continuity in experiences and enabling effective transitions

- analysing, assessing, monitoring and evaluating children’s learning, development and wellbeing in ways to understand, acknowledge and document children’s progress and their achievement of Learning Outcomes.

(EYLF) Holistic, integrated and interconnected approaches

Holistic approaches recognise the integration and connectedness of all dimensions of children’s learning, development and wellbeing. When educators take a holistic approach, they pay attention to children’s physical, personal, social, emotional and spiritual wellbeing and cognitive aspects of learning. They are attuned to children’s actions and promote embodied learning, understanding that children’s minds and bodies are intertwined in the learning process. In this approach children’s voices, actions and movements are important considerations for planning and assessment. While educators may plan or assess with a focus on a particular outcome or component of learning, they see children’s learning as integrated and interconnected. They recognise the connections between children, families and communities and the importance of reciprocal relationships and partnerships for learning. They see learning as a social activity and value collaborative learning and community participation.

Educators promote holistic approaches to learning and teaching. They understand the integrated nature of the Framework, and the connection between the various elements of the Framework. The integration of the Vision, Principles, Practices and Learning Outcomes are key to providing for children’s holistic learning. When planning, teaching and assessing learning, educators engage with all of these elements, thinking about the principles underpinning their practices and the impact of their practices on children’s engagement and achievement in learning, development and wellbeing.

An integrated, holistic approach to teaching and learning also focuses on connections to the natural world. Educators foster children’s capacity to understand and respect the natural environment and the interdependence between people, plants, animals and the land.

(EYLF) Responsiveness to children

Educators are attuned to, and respond in ways that best suit, each child’s strengths, capabilities and curiosity. Knowing, valuing and building on all children’s strengths, skills and knowledge strengthens their motivation and engagement in learning. Educators are aware of, and respond to, the strategies used by children with additional needs to negotiate their everyday lives. They respond to children’s expertise, cultural traditions and ways of knowing, and the multiple languages spoken by some children, including by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children. Educators are also responsive to children’s funds of knowledge (experiences and understandings), ideas, sociality and playfulness, which form an important basis for curriculum decision-making. In response to children’s evolving ideas and interests, educators assess, anticipate and extend children’s learning, development and wellbeing via open-ended questioning, providing feedback, challenging their thinking and guiding their learning. Educators are attuned to, and actively listen to, children so they can respond in ways that build relationships and support children’s learning, development and wellbeing. They make use of planned and spontaneous ‘teachable moments’ to scaffold children’s learning.

Responsive learning relationships are strengthened as educators and children learn together and share decisions, respect and trust. Responsiveness enables educators to respectfully enter children’s play and ongoing projects, stimulate their thinking and enrich their learning.

(EYLF) Play-based learning and intentionality

Play-based learning approaches allow for different types of play and recognise the intentional roles that both children and educators may take in children’s learning. When children play with other children and interact with adults, they create relationships and friendships, test out ideas, challenge each other’s thinking and build new understandings. Play provides both a context (a place or space where children play) and a process (a way of learning and teaching) where children can ask questions, solve problems and engage in critical thinking. Play-based learning provides opportunities for children to learn as they discover, create, improvise and imagine.

Play-based learning with intentionality can expand children’s thinking and enhance their desire to know and to learn, promoting positive dispositions towards learning.

Children act intentionally and with agency in play. This is demonstrated when children make decisions, and with what and with whom to engage and invite into their play. Neural pathways and connections in the brain are stimulated when children are fully engaged in their play as they make plans, create characters, solve problems, develop self-awareness and learn how to socialise, negotiate and think with others. Children’s immersion in their play illustrates how play enables them to simply enjoy being.

Educators are intentional in all aspects of the curriculum and act deliberately, thoughtfully and purposefully to support children’s learning through play. They recognise that learning occurs in social contexts and that joint attention, interactions, conversations and shared thinking are vitally important for learning.

Educators act with intentionality in play-based learning when they, for example:

- plan and create environments both indoor and outdoor that promote and support different types of play for children’s active engagement, agency, problem solving, curiosity, creativity and exploration

- take different roles in children’s play or make purposeful decisions about when to observe and when to join and guide the play

- extend children’s learning using intentional teaching strategies such as asking questions, explaining, modelling, speculating, inquiring and demonstrating to extend children’s knowledge, skills and enjoyment in thinking and learning

- sustain, extend, challenge and deepen children’s ideas and skills through shared thinking and scaffolding learning

- use a range of strategies to plan, document and assess children’s learning in play-based experiences

- plan and implement worthwhile play-based learning experiences using children’s interests, curiosities and funds of knowledge

- assist children to recognise unfair play and offer constructive ways to build a caring, fair and inclusive learning community

- act as resourceful and respectful co-learners and collaborators with children

- support children’s progress in play-based learning through the thoughtful extension of children’s knowledge, skills and concept development

- notice and work sensitively with very young children’s intentions in exploring, practicing and experimenting through play

- acknowledge children’s enjoyment and sense of fun and playfulness in learning, particularly when engaged in group play

- provide a balance between child-led and adult initiated and guided play

- plan opportunities for intentional knowledge building, as well as recognising and utilising opportunities for spontaneous teaching and learning

- use routines, rituals and transitions to foster learning, development and wellbeing

- join in with children’s play experiences, such as taking a role in children’s pretend play, to understand and build on children’s ideas to support and foster learning

- facilitate the integration of popular culture, media and digital technologies which add to children’s multimodal play.

(EYLF) Learning environments

Learning environments include physical, temporal, social and intellectual elements. Welcoming, safe and inclusive indoor and outdoor learning environments reflect, respect, affirm the identities, and enrich the lives of children and families. Educators plan and provide both active and calming spaces, as well as times in the daily schedule for active and quiet play. They provide individual as well as group spaces that respond to children’s interests and capabilities. Environments that support learning are vibrant and flexible spaces that are responsive to the strengths, culture, languages, interests and capabilities of each child, and reflect aspects of the local community. Well planned environments cater for different learning capacities and learning styles and allow for reasonable adjustments where required. Educators also invite children and families to contribute their ideas, interests and questions to create unique and familiar environments. For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families, these contributions can assist in building an intercultural space where both Western and traditional Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander knowledges are shared.

Outdoor learning spaces are a feature of Australian learning environments. They offer a vast array of possibilities for physical activity and learning experiences not available indoors. Access to play spaces in natural environments may include plants, trees, edible gardens, open spaces, sand, rocks, mud, water and other elements from nature. These and other outdoor spaces invite open-ended play and interactions, physically active play and games, spontaneity, risk-taking, exploration, discovery and connection with nature. They foster an appreciation of the natural world and the interdependence between people, animals, plants, lands and waters providing opportunities for children to engage with all concepts of sustainability through environmental education.

Educators where possible participate and offer opportunities for children to learn on Country and seek more information about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander connections and relationships with Country. All children benefit from learning on Country and from Country. For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children, their spirituality is connected to Country, and the connection is strong. It is in their relationships and how they communicate with their ancestors, families, kinship systems and communities. It is in their connection to the land – the trees, waterholes and mountains.

Indoor and outdoor environments support all aspects of children’s learning and invite conversations between children, educators, families and the broader community. They promote opportunities for sustained shared thinking and collaborative learning. Children should experience sustained, appropriate periods of time in both the outdoor and indoor environment for optimal learning to occur. Approved providers and educators are aware that the accessibility of resources and the way in which learning spaces are set up may enable some children and prevent others from participating. In this way approved providers and educators attend to all aspects of the environment to enable all children to participate, succeed in learning and develop positive feelings of self-worth.

Materials enhance learning when they reflect what is natural and familiar, and introduce novelty to provoke interest and more complex and increasingly abstract thinking. For example, digital technologies and media can enable children to access global connections and resources and encourage new ways of thinking. Environments and resources can also highlight our responsibilities for a sustainable future and promote children’s understanding about their responsibility to care for the environment. They can foster hope, wonder and knowledge about the natural world, as well as thinking about social and economic sustainability.

Educators can encourage children and families to contribute ideas, interests and questions to the learning environment. They can support engagement by allowing time for meaningful interactions, by providing a range of opportunities for individual and shared experiences, and by finding opportunities for children to actively participate and contribute to their local community.

(EYLF) Cultural responsiveness

Educators who are culturally responsive, respect multiple cultural ways of knowing, doing and being and celebrate the benefits of diversity. They honour differences and take action in the face of unfairness or discrimination. Being culturally responsive includes a genuine commitment to embed Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander perspectives in all aspects of the curriculum. Being culturally responsive also includes respecting and working collaboratively with culturally and linguistically diverse children and families. Cultural responsiveness is evident in everyday practice when educators demonstrate an ongoing commitment to developing their own cultural knowledge in a three-way process with children, families and communities.

Educators view culture and the context of the child’s family and wider community as central to children’s sense of being and belonging, and their successful lifelong learning. They assist children to be culturally competent and responsive by taking actions in the face of unfairness and discrimination. Educators collaborate with children, their families and members of the community to build culturally safe and secure environments and use this knowledge to inform their practice.

Cultural responsiveness is more than awareness of cultural differences. It includes learning about multiple perspectives and diversity in all its forms, such as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, ethnic, cultural, linguistic, family and individual diversity. It is the ability to understand, communicate with and effectively interact with people across cultures. Cultural responsiveness encompasses:

- awareness of one’s own world view and biases

- respect for diverse cultures

- respect for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures as the nation’s custodians of the land

- gaining knowledge of cultural practices and world views

- communicating effectively and sensitively with people, recognising diverse ways of communicating and interacting across cultures

- everyday practices, including routines and rituals

- decisions and actions that are responsive to children and families’ context.

Culturally responsive educators are:

- knowledgeable of each child and family’s context

- active in embedding Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander perspectives in all aspects of the curriculum

- implementing anti-bias approaches, including social justice approaches to address racism/bias in the setting/community

- embedding democratic and fair practices in their setting, including the importance of being a responsible citizen

- supporting children to take culturally responsive actions in the face of unfairness/discrimination

- collaborating with colleagues, children, families and their communities to build culturally safe learning spaces.

(EYLF) Continuity of learning and transitions

Children bring their individual, family and community ways of being, belonging and becoming, often called funds of knowledge, to their early childhood settings. Educators who know and build on children’s funds of knowledge help them to feel secure, confident and connected to familiar people, places, events and understandings. This reinforces each child’s sense of belonging. Children, families, educators and teachers in schools all contribute to successful transitions between settings.

Children’s identities change as they move from one setting to another. Educators assist children to negotiate changes in their status or identities, for example, when they move to a new room in their early childhood setting or begin full-time school. As children make major transitions to new settings (including to school) educators from early childhood settings and schools commit to sharing information about each child’s knowledge and skills so learning can build on foundations of earlier learning.

Transitions can be everyday occurrences between routines, play spaces or settings, as well as bigger transitions including from home to starting at school or an early childhood setting, or from one early childhood setting to another. All transitions offer opportunities and challenges. Different places and spaces have their own purposes, expectations and ways of doing things. In partnership with children and families, educators ensure that all children have an active role in preparing for transitions. They assist children to understand the traditions, routines and practices of the settings to which they are moving and to feel comfortable with the process of change.

Continuity is where children experience familiar or similar ways of being, doing and learning from one setting to another. Experiencing greater continuity assists effective and positive transitions. Educators work with families to promote continuity, for example, knowing about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children’s kinship connections, parenting practices and other aspects of cultural life can inform positive transitions. Continuity between home and the early childhood setting is important for families as well as children. Continuity in the transition to school can be supported through discussions, access to familiar materials and routines, and timetables that facilitate greeting and departure rituals. Some families and children will need more support when they transition into an early childhood setting or school. Educators work collaboratively with each child’s new educator, teachers in schools and other professionals to ensure a successful transition.

(EYLF) Assessment and evaluation for learning, development and wellbeing

Assessment and evaluation are part of an ongoing cycle that includes observing, documenting, analysing, planning, implementing and critical reflection. Assessment refers to the gathering of information about children’s learning, development and wellbeing, undertaken over time using a range of strategies. Evaluation refers to educators’ critical reflection on and analysis of this information, and consideration of the effectiveness of their planning and implementation of curriculum for children’s learning. Using assessment and evaluation information, educators in collaboration with children, families and other professionals formulate short and long-term learning goals for each child.

(EYLF) Assessment

Assessment strategies are selected by educators for different purposes. Assessment strategies include observations, documentation, reflections and gathering of information about, and with, children and their families. Through assessment, educators describe and interpret children’s actions, interactions and communications to consider their achievements, capabilities and wellbeing in relation to the Learning Outcomes. Educators understand the importance of including children’s voices and contributions to assessment. Assessment strategies that are inclusive, culturally and linguistically relevant, and responsive to the physical, emotional, social, intellectual and regulatory capabilities of each child will acknowledge each child’s abilities, strengths and competencies. Through assessment, educators recognise and celebrate not only the giant leaps children take in their learning but the small steps as well.

Educators utilise 3 broad types of assessment.

- Assessment ‘for children’s learning’, also known as formative assessment, is when information about what children know, can do and understand is gathered and analysed to inform pedagogy and planning. Educators use a variety of strategies to collect rich and meaningful information that depicts children’s learning in context, describes their progress and identifies their strengths, learning dispositions, skills and understandings. Used effectively, formative assessment strategies can capture the different pathways that children take in their learning journeys and make the process of learning visible to children and their families, educators and other professionals.

- Assessment ‘of children’s learning’, also known as summative assessment, is when educators review children’s achievements and capabilities at specified or selected timepoints, such as during their transition into the early childhood setting, mid-year, or for their transition to school. Educators make professional judgements about children’s learning progress over time, to show the ‘distance travelled’ by learners. In their summative assessments, educators can critically reflect on how children have engaged with increasingly complex ideas and participated in increasingly sophisticated learning experiences. Summative assessment can also be based on children’s attainment of developmental milestones, which can be helpful if educators have a concern about a child’s learning abilities or wellbeing. Educators can use such information to start a conversation with families and for potential referral to other professionals for diagnostic assessment.

- Assessment ‘as learning’ is used to facilitate children’s awareness, contributions and appreciation of their own learning. Children’s voices and contributions to assessment can be captured using strategies such as child portfolios or ‘talking and thinking floorbooks’ to involve children in documenting learning. This allows children to reflect on their learning and develop an understanding of themselves as learners, what they like to learn, and how they learn best. When children, families and other professionals are included in the development and implementation of relevant and appropriate assessment processes, new understandings can emerge that would not be possible if educators rely solely on their own perspectives. Developing inclusive assessment practices with children and their families demonstrates respect for diversity, and helps educators, families and children make better sense of the assessment information. Assessment undertaken in collaboration with families can assist them to support children’s learning and empower families to act on behalf of their children within and beyond the early childhood setting.

(EYLF) Evaluation

Evaluation practices involve educators’ critical reflection on the effectiveness of their planning and implementation of curriculum for children’s learning as part of the planning cycle, both for and with children. Evaluation practices can also involve gathering feedback from families. Evaluation focuses on improving aspects of practice to amplify children’s learning, such as learning, teaching and assessment strategies, the environment, use of resources or time. Educators’ evaluations and critical reflection can be undertaken through strategies including review and discussion with colleagues, watching others practice, coaching and mentoring and professional journalling.

Educators critically reflect when they pose questions about new ways of thinking and doing in their evaluations, such as: ‘How effective, meaningful, and relevant was the planned program?’; ‘What difference did we make, and for whom?’ They critically reflect on their own views and understandings of theories, worldviews, evidence-based research, and practice to focus on:

- the experiences, resources, strategies and environments they provide and how these link to the intended Learning Outcomes

- the effectiveness of learning opportunities, environments and experiences offered, and the approaches taken to enable children’s learning

- the extent to which they know and value the culturally specific knowledge about children and learning that is embedded within the community in which they are working

- each child’s learning in the context of their families and children’s funds of knowledge so that the learning opportunities and experiences offered build on what children already know and bring to the early childhood setting

- questioning assumptions and unacknowledged biases about children’s learning and expectations for children

- incorporating pedagogical practices that reflect knowledge of diverse perspectives and contribute to children’s wellbeing and successful learning and is inclusive and appropriate for each child or small groups of children.

Evaluation enables educators in early childhood settings to review how well they are doing, learn from their experience, identify gaps and priorities. Educators consider how they could build on successes and take action to improve their practices

(EYLF) THE EARLY YEARS LEARNING FRAMEWORK PLANNING CYCLE

Diagram 2

The planning cycle describes the process educators follow in planning, documenting, responding to and supporting children’s learning. Educators make many decisions about curriculum planning based on their professional knowledge, their knowledge of children and local contexts, and their understanding of the Vision, Principles, Practices and Learning Outcomes of the Framework. The steps, sequences and components of the planning cycle that are identified and explained in Diagram 2 can occur spontaneously, ‘in the moment’, throughout the day or over a period. Educators use these 5 components to inform their thinking about children’s experiences and improvement of practice to develop and implement a curriculum that is inclusive of all children.

It is important to note that documentation occurs at every stage of the planning cycle.

OBSERVE / Listen / Collect informationEducators use multiple sources of information to gather and document different aspects of children’s learning, development and wellbeing. This can be undertaken across the whole curriculum and throughout the day, including during routines, planned and unplanned experiences, and interactions with peers, family members and other adults. | |

ASSESS / Analyse / Interpret learning

| |

PLAN / Design

| |

IMPLEMENT / Enact

| |

EVALUATE / Critically reflect

|

(EYLF) LEARNING OUTCOMES

The 5 Learning Outcomes are designed to capture the integrated and complex learning and development of all children across the birth to 5 age range. The Learning Outcomes are:

- Children have a strong sense of identity

- Children are connected with and contribute to their world

- Children have a strong sense of wellbeing

- Children are confident and involved learners

- Children are effective communicators.

The Learning Outcomes are broad and observable. They acknowledge children learn in a variety of ways and vary in their capabilities and pace of learning. Over time children engage with increasingly complex ideas and learning experiences, which are transferable to other situations.

Learning in relation to the Learning Outcomes is influenced by:

- each child’s context, including previous experiences, culture, languages spoken, capabilities, emotional wellbeing, dispositions and learning preferences

- educators’ practices and the early childhood environment

- engagement with each child’s family and community

- the integration of learning across the Learning Outcomes.

Children’s learning is ongoing, and each child will progress towards the Learning Outcomes in different and equally meaningful ways. Learning is not always predictable and linear. Educators plan for each child, small and whole groups with the context and the Learning Outcomes in mind. The following Learning Outcomes demonstrate how the 4 elements of the Framework – Vision, Principles, Practices and Learning Outcomes – combine to guide curriculum decision-making and assessment to promote children’s learning.

Key components of learning in each Outcome are expanded to provide examples of evidence that educators may observe in children as they learn. Examples of practice to promote children’s learning are also included.

There will be many other ways that children demonstrate learning within and across the Learning Outcomes. Educators understand, engage with and promote children’s learning. They talk with families and communities to make locally based decisions, relevant to each child and their community.

There is provision for educators to list specific examples of evidence and practice that are culturally and contextually appropriate to each child and their settings.

The 5 Learning Outcomes are relevant for all children. The guidance provides some examples of how educators may work to promote these outcomes and how children’s learning may be evident. When using the Learning Outcomes for planning, educators can modify them to meet the requirements of learners in their learning spaces. Approved providers and educators have inclusion obligations under the Disability Discrimination Act and the Racial Discrimination Act and make reasonable adjustments for all Learning Outcomes to ensure learning engagement for all children. It is acknowledged that children come to the setting with different funds of knowledge, skills and dispositions. Very young and older children are growing, developing and learning in individual ways and may demonstrate the Learning Outcomes differently. Educators’ knowledge of individual children, their strengths and capabilities will guide professional judgement to ensure all children are engaging in a range of experiences across all the Learning Outcomes in ways that optimise their learning. They are committed to equity, inclusion and have high expectations for every child regardless of their circumstances and capabilities.

(EYLF) Learning outcome 1

Children have a strong sense of identity

|

Belonging, being and becoming are integral parts of identity.

A healthy identity is the cornerstone to children’s learning, development and wellbeing. Children learn about themselves and construct their own identity within the context of relationships with other children, their families and communities. This includes their relationships with people, places and things, and the actions and responses of others. Identity is not fixed and changes over time, shaped by experiences. Children can have multiple identities as they move from one setting to another. When children have positive experiences and can exercise agency, they develop an understanding of themselves as significant, respected and feel a sense of belonging. Feeling valued, successful and accepted enables all children to tackle new things, express themselves, work through differences and take calculated risks. Educators are culturally responsive in assisting all children to explore their cultural, social, gender and linguistic identities. Relationships are the foundations for the construction of identity – ‘Who I am’, ‘How I belong’ and ‘What is my influence?’ Relational pedagogy underpins the interactions between educators, families and children and is key to children building a positive sense of self-worth. Children come to know themselves, developing their identity through relationships and interactions with others, engaging in life’s complexities and joys, and learning how to meet challenges encountered in everyday life.

In early childhood settings all children develop a sense of belonging when they feel accepted, develop secure relationships and trust those who care for them. As children are developing their sense of identity, they explore different aspects of it (physical, social, emotional, spiritual, cognitive) through their play and their relationships and friendships.

When children feel safe, secure and supported they grow in confidence to explore and learn. Identity and confidence are also built when all children are offered genuine choices, time and opportunity to exercise agency, act on their own to increase autonomy, resilience and persistence, as well as interact with others with care, empathy and respect. The concept of being reminds educators to focus on children in the here and now, and of the importance of children’s right to be a child and experience the joy of childhood. Being involves children developing an awareness of their social, linguistic and cultural heritage, of gender and their significance in their world. For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children, awareness of their kinship networks and connections to Country are important to development of identity.

Becoming includes children building and shaping their identity through their evolving experiences and relationships which include change and transitions. Children are always learning about the impact of their personal beliefs and values. Children’s agency as well as guidance, care and teaching by families and educators shape children’s experiences of becoming.

(EYLF) Children feel safe, secure and supported

Children feel safe, secure and supported. | |

This is evident when children, for example:

| Educators promote this learning for all children when they, for example:

|

(EYLF) Children develop their emerging autonomy, inter-dependence, resilience and agency

Children develop their emerging autonomy, inter-dependence, resilience and agency | |

This is evident when children, for example:

| Educators promote this learning for all children when they, for example:

|

(EYLF) Children develop knowledgeable confident self-identities, and a positive sense of self-worth

Children develop knowledgeable confident self-identities, and a positive sense of self-worth. | |

This is evident when children, for example:

| Educators promote this learning for all children when they, for example:

|

(EYLF) Children learn to interact in relation to others with care, empathy and respect

Children learn to interact in relation to others with care, empathy and respect. | |

This is evident when children, for example:

| Educators promote this learning for all children when they, for example:

|

(EYLF) Learning outcome 2

Children are connected with and contribute to their world

|

Experiences of relationships and participation in communities contribute to children’s belonging, being and becoming. From birth children experience living and learning with others in a range of communities. These might include families, local communities or early childhood settings. Having a positive sense of identity and experiencing respectful, responsive relationships strengthens children’s interests, knowledge and skills in being and becoming active contributors to their world. As children move into early childhood settings, they broaden their experiences as participants in different relationships and communities.

Over time the variety and complexity of ways in which children connect and participate with others increases. Very young children participate through smiling, moving, imitating, gesturing and making sounds to show their level of interest in relating to or participating with others. As children grow, they develop more complex ways of connecting and communicating with others. Older children show interest in how others regard them and develop their understandings about friendships. They learn to appreciate that their actions or responses affect how others feel or experience belonging. Feelings of belonging strengthen children’s connection with and active contribution to their world. Belonging includes people, Country, place and communities where educators assist all children to explore values, traditions and practices of their own and others’ families and communities.

When educators create environments in which all children experience mutually enjoyable, caring and respectful relationships with people and the environment, children respond in positive ways. When all children participate collaboratively in everyday routines, events and experiences and have opportunities to contribute to decisions, they learn to live interdependently.

Children’s connectedness and different ways of belonging with people, Country and communities helps them to learn ways of being which reflect the values, traditions and practices of their families and communities. Over time this learning transforms the ways they interact with others.

Children are increasingly connecting with others through digital contexts. The use of digital technologies and the internet includes sharing and communicating information, enabling children to connect and contribute to their world in new ways. Educators use evidenced-based knowledge to assist children and families in using digital technologies in safe and healthy ways.

Children’s connection and contribution to their world is built on the idea they can exert agency in ways that make a difference and build a foundation for civic and democratic participation. Educators assist all children to explore notions of sustainability (social, economic and environmental) where children learn what they do can make a difference. Environmental sustainability focuses on caring for our natural world. Social sustainability is about living peacefully, fairly and respectfully together in resilient local and global communities. Economic sustainability refers to practices that support economic development without negatively impacting the other dimensions. This includes a focus on fair and equitable access to resources, conserving resources, and reducing consumption and waste.

Educators know that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures are strongly tied to the land and often there are cultural expectations and considerations that may transform the way they interact with others and the environment. Educators are sensitive to this and work to build trusting relationships with families, Elders and communities so that histories, stories, languages, as well as the local knowledge of how the Traditional Owners cared for and sustained the land, are shared with all children.